| Story Title | Book | Classification Within Book |

| John & The Devil’s Daughter | The People Could Fly | |

| The Peculiar Such Thing | The People Could Fly | |

| Little Eight John | The People Could Fly | |

| Jack and the Devil | The People Could Fly | |

| Better Wait Till Martin Comes | The People Could Fly | |

| Wiley & The Hairy Man | A Treasury of Afro-American Folklore | “Testing Wits: Human v. Demon” |

| Judge Foolbird | A Treasury of Afro-American Folklore | “Justice, Injustice, and Ghosts in the Swamps of the Congaree” |

| The Settin’ Up | A Treasury of Afro-American Folklore | “Justice, Injustice, and Ghosts in the Swamps of the Congaree” |

| The Little Old Man on the Gray Mule | A Treasury of Afro-American Folklore | “Justice, Injustice, and Ghosts in the Swamps of the Congaree” |

| The Lake of the Dead | A Treasury of Afro-American Folklore | “Justice, Injustice, and Ghosts in the Swamps of the Congaree” |

| Murder vs. Liquor | A Treasury of Afro-American Folklore | “Justice, Injustice, and Ghosts in the Swamps of the Congaree” |

| Old Dictodemus | A Treasury of Afro-American Folklore | “Justice, Injustice, and Ghosts in the Swamps of the Congaree” |

| Old Man Rogan | A Treasury of Afro-American Folklore | “Justice, Injustice, and Ghosts in the Swamps of the Congaree” |

| The Yellow Crane | A Treasury of Afro-American Folklore | “Justice, Injustice, and Ghosts in the Swamps of the Congaree” |

| Ruint | A Treasury of Afro-American Folklore | “Justice, Injustice, and Ghosts in the Swamps of the Congaree” |

| Possessed of Two Spirits | Green — African American Folktales | “The Supernatural” |

| Ridden by the Night Hag | Green — African American Folktales | “The Supernatural” |

| The Hunter and the Little Red Man | Green — African American Folktales | “The Supernatural” |

| The Friendly Demon | Green — African American Folktales | “The Supernatural” |

| Courted by the Devil | Green — African American Folktales | “The Supernatural” |

| Married to a Boar Hog | Green — African American Folktales | “The Supernatural” |

| Wait Til Emmet Comes | Green — African American Folktales | “The Supernatural” |

| Jean Lavallette and the Curse of the Homme Rouge | Green — African American Folktales | “The Supernatural” |

| The Devil’s Bride Escapes | Green — African American Folktales | “The Supernatural” |

| Aunt Harriet | Green — African American Folktales | “The Supernatural” |

| The Stolen Voice | Green — African American Folktales | “The Supernatural” |

| 81 | American Negro Folktales | “Hoodoos and Two-Heads” |

| 82 | American Negro Folktales | “Hoodoos and Two-Heads” |

| 83 | American Negro Folktales | “Hoodoos and Two-Heads” |

| 84 | American Negro Folktales | “Hoodoos and Two-Heads” |

| 85 | American Negro Folktales | “Hoodoos and Two-Heads” |

| 86 | American Negro Folktales | “Hoodoos and Two-Heads” |

| 87 | American Negro Folktales | “Hoodoos and Two-Heads” |

| 88 | American Negro Folktales | “Hoodoos and Two-Heads” |

| 89 | American Negro Folktales | “Hoodoos and Two-Heads” |

| 90 | American Negro Folktales | “Hoodoos and Two-Heads” |

| 91 | American Negro Folktales | “Hoodoos and Two-Heads” |

| 92 | American Negro Folktales | “Hoodoos and Two-Heads” |

| 93 — Becoming a Two-Head | American Negro Folktales | “Hoodoos and Two-Heads” |

| 94 | American Negro Folktales | “Hoodoos and Two-Heads” |

| 95 | American Negro Folktales | “Hoodoos and Two-Heads” |

| 96 | American Negro Folktales | “Hoodoos and Two-Heads” |

| 97 | American Negro Folktales | “Hoodoos and Two-Heads” |

| 98 | American Negro Folktales | “Hoodoos and Two-Heads” |

| 99 | American Negro Folktales | “Hoodoos and Two-Heads” |

| 100 | American Negro Folktales | “Hoodoos and Two-Heads” |

| 101 | American Negro Folktales | “Hoodoos and Two-Heads” |

| 102 | American Negro Folktales | “Spirits and Hants” |

| 103 | American Negro Folktales | “Spirits and Hants” |

| 104 | American Negro Folktales | “Spirits and Hants” |

| 105 | American Negro Folktales | “Spirits and Hants” |

| 106 | American Negro Folktales | “Spirits and Hants” |

| 107 | American Negro Folktales | “Spirits and Hants” |

| 108 | American Negro Folktales | “Spirits and Hants” |

| 109 | American Negro Folktales | “Spirits and Hants” |

| 110 | American Negro Folktales | “Spirits and Hants” |

| 111 | American Negro Folktales | “Spirits and Hants” |

| 112 | American Negro Folktales | “Spirits and Hants” |

| 113 | American Negro Folktales | “Spirits and Hants” |

| 114 | American Negro Folktales | “Spirits and Hants” |

| 115 | American Negro Folktales | “Spirits and Hants” |

| 116 | American Negro Folktales | “Spirits and Hants” |

| 117 | American Negro Folktales | “Spirits and Hants” |

| 118 | American Negro Folktales | “Spirits and Hants” |

| 119 — “Eating the Baby” | American Negro Folktales | “Spirits and Hants” |

| 142 — Devil’s Daughter | American Negro Folktales | “The Lord and the Devil” |

| 155 | American Negro Folktales | “Horror” |

| 156 | American Negro Folktales | “Horror” |

| 157 | American Negro Folktales | “Horror” |

| 158 | American Negro Folktales | “Horror” |

| 159 | American Negro Folktales | “Horror” |

| 160 | American Negro Folktales | “Horror” |

| 161 | American Negro Folktales | “Horror” |

| 162 — Embalming a Live Man | American Negro Folktales | “Horror” |

| 163 | American Negro Folktales | “Horror” |

| 164 | American Negro Folktales | “Horror” |

| 165 | American Negro Folktales | “Horror” |

| 166 | American Negro Folktales | “Horror” |

| 192 — Waiting for Rufus | American Negro Folktales | “Scare Tales” |

| 193 — Waiting for Martin | American Negro Folktales | “Scare Tales” |

| 194 | American Negro Folktales | “Scare Tales” |

| 195 | American Negro Folktales | “Scare Tales” |

| 196 | American Negro Folktales | “Scare Tales” |

| 197 | American Negro Folktales | “Scare Tales” |

| 198 | American Negro Folktales | “Scare Tales” |

| The Ways of a Witch | Talk that Talk | “The Bogey Man’s Gonna Git You” |

| The Two Sons | Talk that Talk | “The Bogey Man’s Gonna Git You” |

| Taily Po | Talk that Talk | “The Bogey Man’s Gonna Git You” |

The Folktales

Work-In-Progress Blog

Blog #1 — Haunting & Cultural Memory

Preparing for the April 6th “Mini-Festival,” I began to do readings into the history of African-American folklore, its cultural and personal, and, specifically, its relationship to ghosts. Although my initial question was “what does and African American horror tradition look like,” I quickly narrowed my focus. Instead of generally considering “horror,” I would look instead at ghosts and concepts of haunting, both of which operate as a site of terror in the present, while reaching back to the horrors of the past. Most “horror stories” tend to focus on ghosts, or spirits, or reincarnation, so this is less of a tightening of my purview and more of a clarifying of language.

Although ghosts appear in many (most?) cultures, American ghosts are directly tied into historical memory. In his essay “‘Haints’: American Ghosts, Ethnic Memory, and Contemporary Fiction,” Arthur Redding quotes D.H. Lawrence, who wrote, “America hurts because it has a powerful disintegrative effect on the white psyche. It is full of grinning, unappeased aboriginal demons, too, ghosts, and it persecutes the white men” (165). Of course, this is why white America is haunted, but I wonder if black American has similar ghosts. Maybe the demons aren’t coming back for retributions against wrongs done by the literal master class, but maybe they’re memories of a collective trauma?

Why is haunting significant? I look to Avery Gordon (quoted in Redding) who writes in her book Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination, “haunting rather than history (or historicism) best captures the constellation of connections that charges any ‘time of the now’ with the debts of the past and the expense of the present” (142).

Ghosts, for her, for Redding, for many passing on the tradition of African American folktales, and for me, convey both baseless terror and some kind of message. In her essay “American Stories of Cultural Haunting: Tales of Heirs and Ethnographers,” Kathleen Brogan discusses the implications of haunting. She argues that the most “most dreadful of these implications is that the haunting is not entirely voluntary; we can’t always choose our ghosts. The attractive possibility of adopting beneficent ancestors might suggest that ethnicity is freely and consciously constructed, but in fact these choices are often experienced as mysterious mandates. Haunting metaphors forcefully convey the reality that cultural transmission operates partly on a subrational level.” (161).

In his essay “‘Haints’: American Ghosts, Ethnic Memory, and Contemporary Fiction,” Redding begins with an epigraph from an Adrienne Rich poem “What Ghosts Can Say.” This excerpt, which introduces his piece concludes her. After the central figure of her poem sees a ghost of his father Rich wonders what the meaning of such an encounter is. She writes,

…What ghosts can say—

Even the ghosts of fathers —comes obscurely.

What if the terror stays without the meaning ?

This is maybe the most terrifying thing about being haunted (or about being a presence that haunts): the lack of agency. Redding paradoxically describes ghosts as “powerful figures of powerlessness” (165), in the same way the living dealing with a spirit has agency over their lives and bodies, but not over their supernatural visitor.

Blog #2: — Why (folklore) & How (to best represent it)

A short note about my own insecurity: Although instinctually I felt that folklore was the right lens through which to approach this project, I felt some anxiety regarding the fact that I am not a folklorist, nor am I an ethnographer nor am I an anthropologist. I’m an English major which means I’m qualified to close read, but not do any large cultural analyses or draw conclusions about ethnic groups based on the content of their stories. Thinking about this project ethically, I think it fails some basic tests: I don’t have time to do a broad survey of previously recorded tales, and so the ones I choose will be representative only of the few dozen works I’ve examined. I also don’t know enough to talk about region distinctions, or even antebellum / post-bellum changes in tales, which, to be fair, no one has, as there were not many ethnographers in the mid 19th century interested enough African American folktales to create a base of stories to then compare to WPA and later attempts to gather oral lore. This is all to acknowledge early this proposal is more ambitious than I had initially thought (back when I still knew it to be ambitious but I was thinking more of the volume of stories than the complex job of an ethnographer).

Back to the blog: I still believe folklore is the best place to start when looking at an African American literary tradition. In his essay “Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner: Folklore, Folkloristics, and African American Literary Criticism” Anand Prahlad quotes Trudier Harris, an English professor at UNC who argues “African-American folklore is arguably the basis for most African-American literature” (565).

Professor Tolagbe Ogunleye writes in her essay “African American Folklore: Its Role in Reconstructing African American History” that “African American folklore offers researchers an invaluable framework for insight into the history and worldview of African Americans” (435) and includes in this categorization of folklore and folktales all orally transmitted lore — myths, storytelling, recollections, ballads, songs, and raps. She quotes Molefi K. Asante “no art form reflects the tremendous impact of our presence in America more powerfully or eloquently than does folk poetry in the storytelling tradition” (435) and Zora Neale Hurston who described folklore as “boiled-down juice of human living.”

Ogunleye continues her argument, writng, “Folklore represents a line to a vast, interconnected network of meanings, values, and cognitions. Folklore contains seeds of wisdom, problem solving, and prophecy through tales of rebellion, triumph, reasoning, moralizing, and satire. All that African American people value, including the agony enslaved and freed Africans were forced to endure, as well as strategies they used to resist servitude and flee their captors, is discernible in this folk literature.” (436).

Regarding the representation of folktales, an oral tradition, in text, the scholars I’ve been reading have much to say. Prahlad argues, “Folklore is worlds away from representational texts found in collections. Rather, it is a part of the body, the unconscious and conscious mind, the spirit, the air that is breathed, the smells, sounds, sensations, and the totality of elements found in given moments of dynamic social interaction. It is a corporeally based, expressive, and artful language and system of thought of which spoken or written words are only a part” (167). Given this, he uses Daniel Barnes’s argument from “Toward the Establishment of Principles for the Study of Folklore and Literature,” where he writes argues that by transcribing folktales we reduce them, and that “The text of a folktale is not ‘the folktale’: but the transcription of an oral performance” (9, Prahland 165).

Although originally I wanted to rewrite amalgamated folktales from other collections, I think, in this, the age of podcasting, it would be appropriate to record myself reading from folktales. I don’t know at this point if that will mean writing my own based on existing ones, or just reading from existing texts. In some ways the perfect presentation of these tales would be a podcast or recording that I prepared for, by memorizing the key points of the story, but consisted of me recounting the story from memory, in a conversational tone. This would be more “true” to the way folktales were originally disseminated, although my concern would be that I would leave out key elements, or that they would be rambling, or that they would not be fun to listen to. As I begin to look at the folktales themselves I’ll consider length, complexity, and my own storytelling abilities, which will help me determine exactly what form my final project will take.

Blog #3 — What we talk about when we talk about horror

(A digression but useful for my own conceptualization of this project)

Working on this project I realized I had never clearly defined horror, moving instead from horror to ghosts without really investigating what that meant. “Haunting” is a useful way of defining the scope of my project, but I’ve been using it as a stand in for all scary stories, and realized it might be useful to consider the ways in which this is and is not accurate — there are many types of scary stories, and seeing how what I’m describing as “the African American Horror Tradition” is useful for my project.

Using the Wikipedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Horror_fiction) listing for literary horror subgenres (and filtering out erotica and genres based around a nationality) the major subgenres are:

Dark fantasy, Body horror, Ghost story, Giallo (thriller, slasher, crime), Gothic, Grotesquerie, Horror-of-demonic, Horror-of-personality, List of werewolf fiction, Lovecraftian horror, Macabre, Monster , Psychological horror, Splatter film, Supernatural fiction, Survival horror, Werewolf, Zombie

Netflix (http://ogres-crypt.com/public/NetFlix-Streaming-Genres2.html), which is known for its specific sub-categorization of film genres, defines Horror genres (again, discounting nationality):

B-Horror Movies , Creature Features, Horror Movies, Deep Sea Horror Movies, Horror Comedy, Monster Movies, Slasher and Serial Killer Movies, Supernatural, Teen Screams, Vampire Horror Movies, Werewolf Horror Movies, Zombie Horror, Movies, Satanic Stories

Horror on Screen, a website dedicated to horror movies, has made a flow chart that breaks horror down into five primary categories: Gore, Psychological, Killer, Monster, and Paranormal (they also include twelve “unsortable” categories including “Creepy Children,” “Gothic,” and “Body Horror,” all categories I would argue could be fit into the five primary categories). This is my favorite breakdown, although I would argue a story can cross boundaries. Paranormal stories often have a Psychological element (Consider Edgar Allen Poe, or Charlotte Gilman Perkins, or anything in the gothic category, which is primarily psychological, with threats of the supernatural).

Maybe more useful is a list of elements from which to shape a work of horror. Instead of a story being defined by a restrictive genre, a story could be described as a scary tale with elements of the paranormal and gore.

The folktales I’m looking at are fairly bloodess, but contain elements of ghost stories, the gothic, demonic horror, psychological horror, possession and the supernatural. Some contain violence, but most contain non-violent encounters with the devil and the dead.

Blog #4 — An annotated bibliography

I’ve begun looking at the folktales themselves! Some books I already know I can return to the library:

African-American Folktales for Young Readers by Richard Young and Judy Dockrey Young is not useful; the stories have been modernized, and it is difficult to tell what elements are “original.”

African-American Folktales: Stories from Black Traditions in the New World by Roger Abrahams is also unhelpful. Although it has many well categorized and well told tales it didn’t have any that could be classified as “scary.”

I have five others that I haven’t read, but seem promising. Talk That Talk: A Anthology of African-American Storytelling by Linda Goss and Marian E. Barnes has a section called “The Bogey Man’s Gonna Git You: Tales of Ghosts and Witches”; African American Folktales edited by Thomas A. Green has a section on the supernatural; American Negro Folktales, compiled by Richard Dorson, has five relevant sections, “Hoodos and Two-Heads,” “Spirits and Hants,” “The Lord and the Devil,” “Horrors,” and “Scare Tales”; Courlander’s A Treasury of African-American Folklore has sections titled “Justice, Injustice, and Ghosts in the Swamps of the Congaree,” and “Testing Wits: Human Versus Demon”; and finally Virginia Hamilton’s The People Could Fly has “John and the Devil’s Daughter and Other Tales of the Supernatural.” I’m excited to start reading!

I was interested reading from Dorson’s prefaces to his sections, especially his note on “Horror,” which mirrors some of my thinking when I began this project. Dorson writes about how, when asking story tellers to share “local traditions, family history, and personal experiences…sometimes these localized and personalized narratives prove to be folktales in disguise.” And how many Southern Black men and women understandably often turn to slavery when they discuss family history. He writes, “Brutal and inhuman acts of slave masters still burn in the breasts of generations born to freedom, fanned by the bellows of tradition (not that all memories of slavery life rankle, but shocking events live longest in the folk mind). Emancipation failed of course to end the injustice of white man to black…and the intimidation of freedmen and their children formed new atrocity stories…any sensationalist crime attracts the folk historian…” (283). I like his separation of real ancestral memories of historical horror, and ghosts, goblins, and scary stories. I’m excited to start reading and see in what ways these categories do and do not overlap.

Kenyon’s Reflection

Summary

In setting out to bring the words of both Walt Whitman and Walter Mosley to life, I did not realize the extent to which I was taking on what has proved to be a thoroughly challenging and fulfilling work. The texts of Futureland and “I Sing the Body Electric” exist, for some, on completely different planes of literature. However, I set out to position these texts together as they form an interesting critique on the issue of Black embodiment. Specifically, these texts form an indictment on the systems of racism that surround Black people in America and point out the hypocrisy of the American ideals held up by Whitman through his poetry by clearly displaying how the act of racializing a body rends it apart from the soul. In other words, when systems of racial oppression operate on a human body, in order to survive the onslaught of ––– Black people sometimes provide themselves with an emotional distance between the way their body is perceived by others and their own personal worth. While this emotional distancing is good in that in many cases it saves lives, it also is a coping mechanism that puts up a barrier between the Black body and the soul that resides there. In this way, Whitman’s philosophies on embodiment are rendered moot for Black people in the shadow of America’s system of racialized oppression.

In reflection, and as I detail the process and results of my project below, I have found that this topic can be quite deftly portrayed through artistic media, like music. However, to engage in a work of art with such an aim is also a huge undertaking, as the issue of clarity in form and in word is of the utmost importance. As I will talk about below, this has been a very fruitful project both personally and academically, but it is also one that has not come without its own set of challenges.

Project Achievements

The Lyric

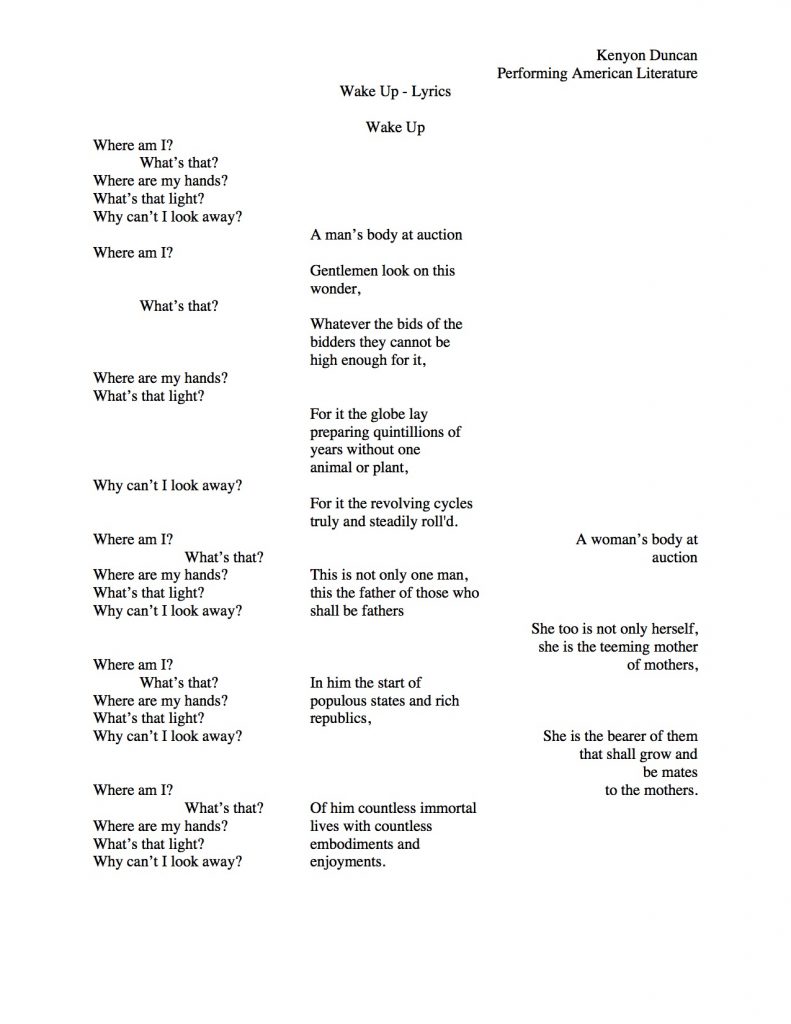

The main achievement of this project rests in the lyrics – which I have attached in two forms. It took an incredible amount of effort to find the common ground that the Whitman and Mosley texts share without the use of regular prose. When constructing the lyrics, therefore, I relied on two criteria in most cases: my sense of the text’s rhythm and clarity of voice. The cadence of the language was used to determine which sections of language to keep adjacent to each other and which to reposition in time. Alternatively, the tone of voice and style of writing informed which sections of writing, internal to each original text, could be maintained or not. For example, the lines that mention or imply the first person – the ‘I’ in Whitman’s poetry – has been left out, and along with it, almost all of the questions, as they almost invariably break the characterization of the auction block atmosphere I am trying to establish at the beginning. From Futureland I included the passages that dialogical in nature. This establishes a clear sense of a person who is singing these lines, rather than a third person account of what is going on. Keeping that narrative arc in first person allows for a direct interpolation of the listener into the narrative of the story, hopefully adding to the emotional weight of the lyric and piece as a whole. In addition, though I did not set any of the prose of Futureland directly to music, I channeled it into my musical understanding of the atmosphere that surrounds the piece. To this effect I’ve included one of the passages that has formed my musical understanding of the piece in the lyric sheet.

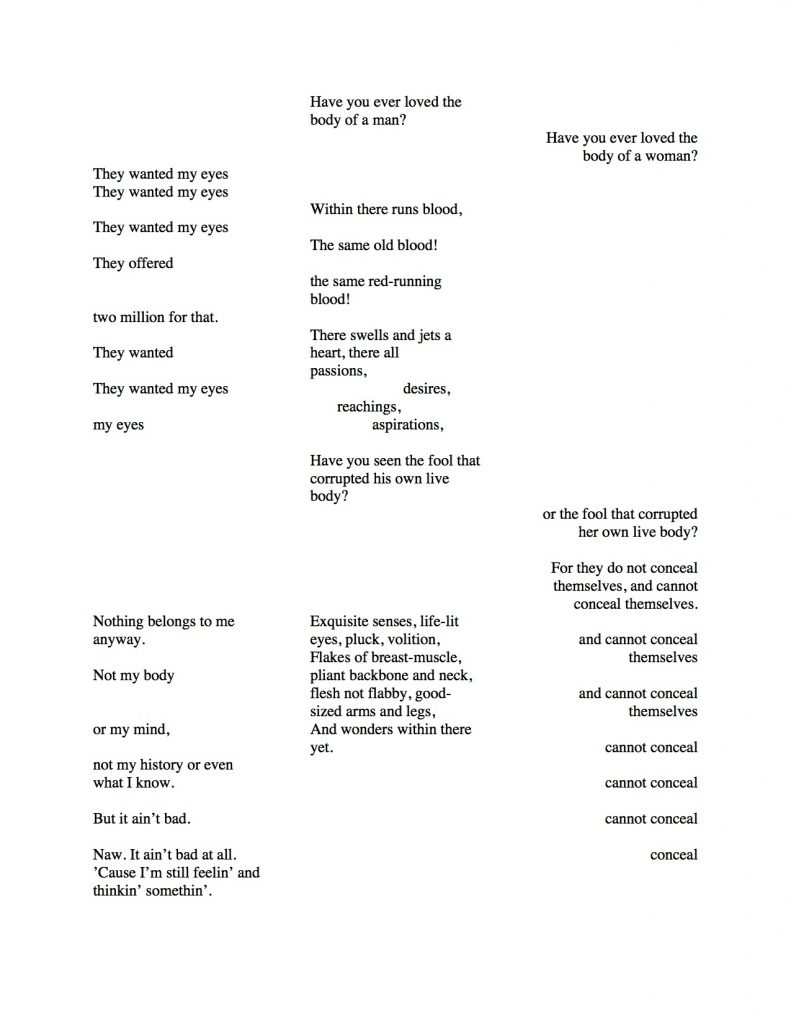

The reason I have included two different layouts of the lyrics here is to highlight the multiple layers of composition that are in textual play with each other. In the typed document format, the lyrics tell a linear story. Starting with excerpts from “Whispers in the Dark” the listener encounters a person who has just been commanded to wake up and does not know where they are, much less the state of their physical body. As the story progresses, the textual insertions of piece of the seventh stanza of “I Sing the Body Electric” position this person as the subject of an auction. As the narrative continues the texts come together to portray the psychophysical damage that our main character (intentionally neither male nor female) incurs by the devaluing of their body. The delayed addition of the 8th Stanza of Whitman’s poem heightens the texture of the piece and also generalizes the conflict from one that is between two people to one that is between a person and the society around them.

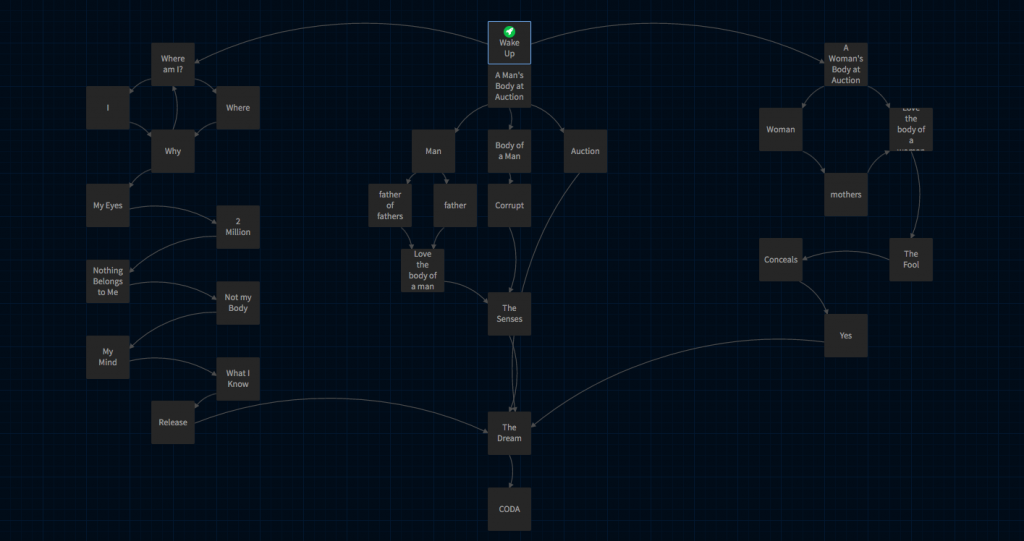

Here is the layout of my lyrics on Twine. If going through the Twine story, you’ll definitely need to play it a couple of times to reach each storyboard

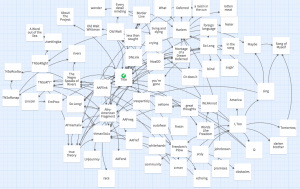

The lyrics on Twine help to elucidate the non-linear elements of this story. As shown in the above image, the connections between each piece of the lyrics are myriad and complicated, however it is in these connections that the real crux of the issue of embodiment can be found. For instance, the repeated words that open the piece “Where am I? What’s that? Where are my hands? What’s that light? Why can’t I look away?” create a linear progression on the typed page but a cyclical occurrence in Twine. This cycle then spins itself out into violence as it is followed by the line “They wanted my eyes.” The Twine representation of the lyric was most useful in the construction process of this project. Though Twine is often used as a means of story presentation and interactivity. It was actually most helpful for me as a storyboarding tool, as it helped me spatially map this story onto itself.

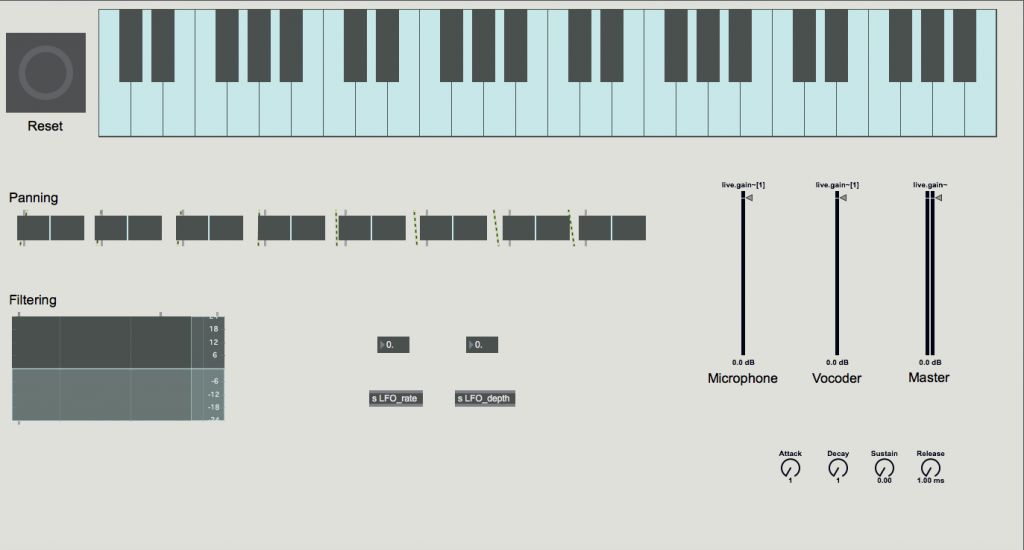

The Music

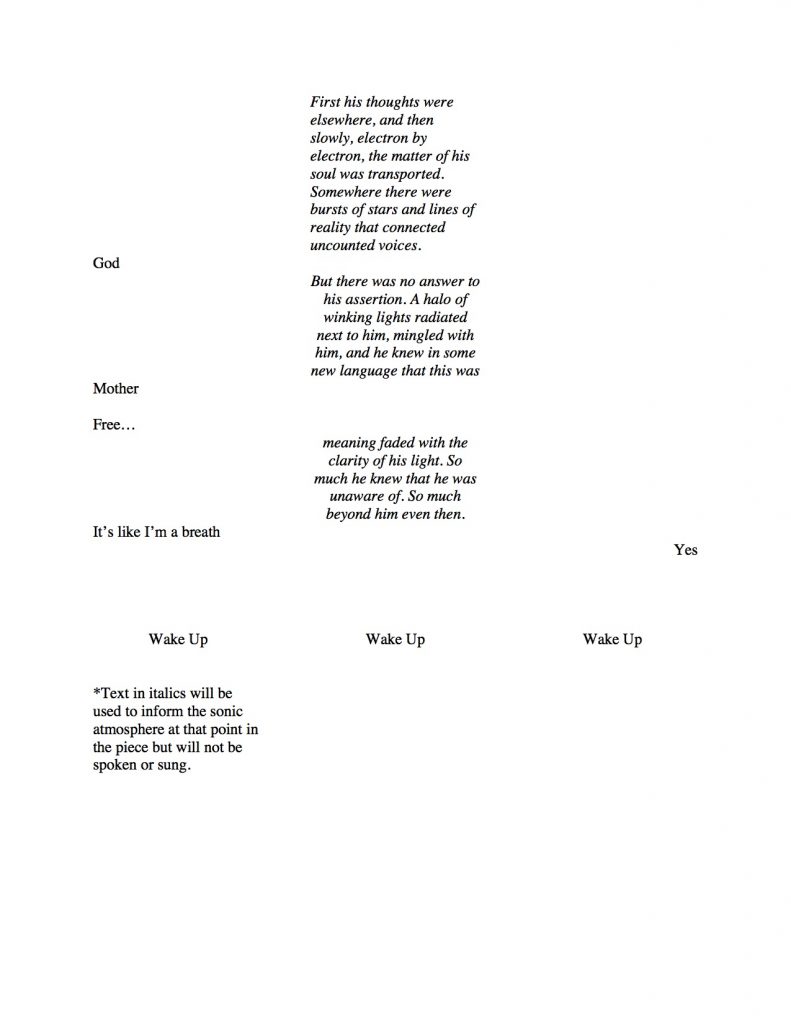

Included above is an image of the first few pages of music for this project. Currently the piece is scored for 1 Baritone singer and two instantiations of the vocoder I spent this semester working on. The same person should perform all of these voices – that of the Baritone and the vocoder(s). As I developed the piece and this stipulation became apparent, it was clear to me that this must be a recorded, digital work only as live performance is impossible. The recorded nature of this project also has enabled me to explore non-natural sounds (other synthesizers, drum samples, reverb/delay effects etc.) In an attempt to represent the rest of this musical content I have also included in my score a piano reduction of the rest of the musical context on which the voices rest.

This project has allowed me to explore my own compositional abilities through the technique of recombination. This methodology was of paramount importance while working on the music as in essence this entire piece is a recombination of two different texts. Musically this translated into driving rhythmic patterns and interlocking musical structures, which also harkens back to some of the Afrofuturist music I posted on my blog.

In keeping with the idea of racism as work that separates the soul from the body, much of the musical language I am incorporating into the piece is intended to evoke the sensation of tearing and ripping – the visceral act of being severed from yourself. This translates into two types of dissonance that are predominant in the texture: harmonic dissonance and rhythmic dissonance. Harmonically, as is depicted in the piano reduction, the main element used is a series of cluster chords – chords that are made of notes very close to each other. This creates the sensation of blur in the texture, mirroring the main vocalist’s lack of direction and self-knowledge. The main form of rhythmic dissonance I employ is syncopation – the act of playing “off the beat.” This dislocation of the rhythm both creates a texture for the vocalist to sing over and also upends the traditional sense of meter, contributing to the confusion apparent at the outset of the piece.

As is expected, especially when dealing with this particular topic, the overall effect is that of violence. Experiencing this piece, as it continues to be written, will be discomforting and overtaking. This is especially important to me as it provides a space for the listener that elucidates some of the violence that is enacted upon the Black body at the hands of America’s political and socio-economic structures.

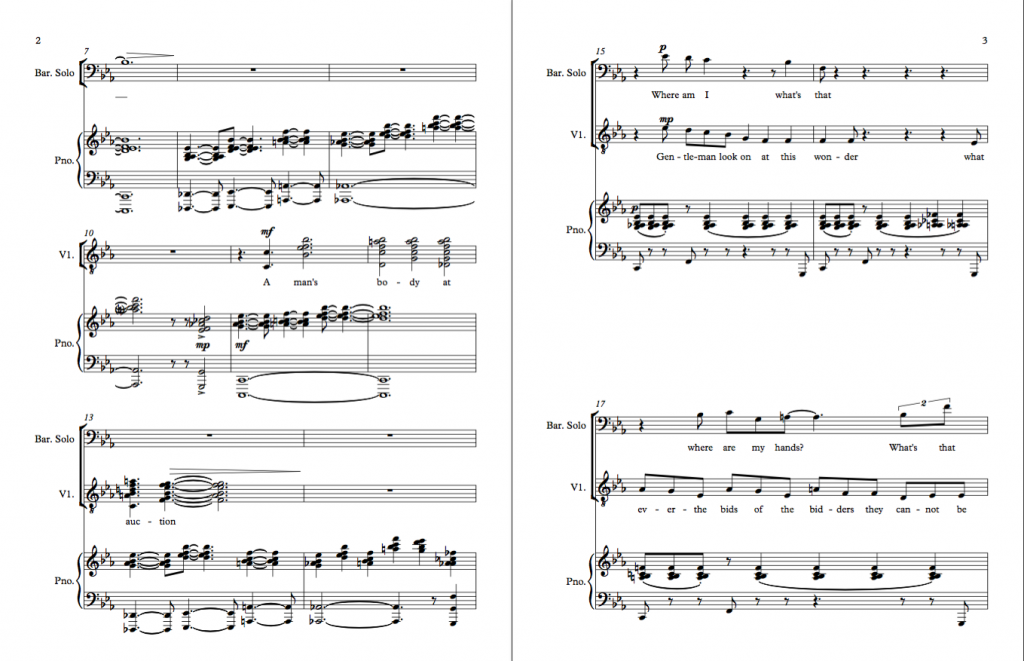

This is the interface for the software vocoder that I created and am using as one of the primary instruments in this project.

The use of the vocoder is perhaps the most thrilling aspect of this project. I have been working on creating a software vocoder for much of the semester, and now that it is finally finished I am so pleased to use it in completing this project. As I alluded to in one of my blog posts, this instrument takes the human voice as input and replicates it at different frequencies. This process combines the distinct and soulful aspects of the human voice and digitizes it in order to manipulate it. In doing so the listener is left with what sounds like something that is almost human and is almost digital. The inclusion of instrument links the piece, aurally, to the tradition of science fiction. More importantly thought, this instrument sonifies the uncertainty of existence that is at the crux of the issue of Black embodiment. It accentuates the voices of those who feel disembodied due to racialization and parallels the struggle of the Black soul as it tries to reconcile itself with a physical form that is systemically rejected. This instrument, in essence, creates the perfect metaphor for the entire piece.

Extensions, Shortcomings & The Future

As I was writing and compiling the music and text, it became apparent that this combination of contemporary science fiction and classic American poetry created a uniquely fascinating junction point, at which the reader/listener is given the opportunity to explore the idea of social progress in this country under a different lens. The tenants of science fiction allow for the genre to always be one that pushes our current understanding of what is technically possible but also socially critical for our continued communal existence. In this way, Futureland does nothing that is earth shattering or groundbreaking by talking about race – there are other science fiction stories that attempt to tackle the same issue. However by pairing it with the text of Whitman, the listener/reader is forced to confront the completely different manifestations of America and American ideals that are in each text.

Because of this, I’m quite interested in continuing this piece to its completion, but also in expanding this project to a song cycle of textual juxtapositions that provide a space for the nuanced and extremely influential aspects of Black life in America. Fortunately, the entire body of American literature, as we have discovered this semester, is equipped to speak to, at least in part, the issue of race in America as it was and is currently inextricable from the environment in which all artists who call themselves American live.

I had originally intended for this project to result in a completed and recorded final version of a setting of these texts. After committing to my methodologies surrounding lyric generation in multiple forms, the completion and addition of my own vocoder as an instrument, and expanding the project further to be a major musical work rather than a 2-3 minute song, I feel as though I have the processes in place to continue this project while preserving the artistic integrity of this performance of these American texts. Expanding on this even further, as this piece hopefully transforms into a song cycle, the exciting opportunity for an interactive live performance of these pieces – complete with the vocoder, live electronic music, and lighting –seems on the horizon. These types of live, theatrical, performances of texts that are continually shaping the American social landscape, calls to me as a standout form in which to experience American literature in our current time.

Laurence’s Reflection

Laurence Bashford Performing American Literature Prof. Wai Chee Dimock Final Project & Reflection Spring 2017

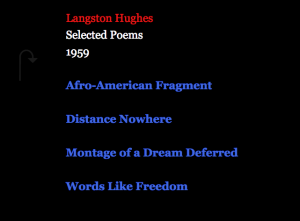

Selected Poems of Langston Hughes: An Interactive Edition

“So Long!” to “Hold On!”: Whitmanian Dreaming & African American Imaginaries

Live project platform available at:

http://philome.la/thelaurenceb/l-hughes-selected-poems–whitmanian-dreaming/

“It is my hope to create a performative and interactive literary project that brings these two poets and their writings to life in dialogue with one another across the centuries. I envision this would take the form of firstly a close-analysis document that uses digital humanities technology to annotate and track the path of poetic influence on a line-by-line basis across both poets’ collated works, drawing primarily on selections from the 1860 Leaves of Grass edition, and Hughes’ 1960 Selected Poems.” – Proposal (03.06.2017)

Summary Reflection:

While my initial designs for this semester’s project had been ambitious beyond the realms of true practicality, I have chosen to highlight this central goal from my earlier proposal as the standard to hold my final-produced digital humanities platform by –– and which I am pleased to say I feel as though I have more or less accomplished, with a couple of key clarifications. The ultimate challenge of technological limitations was bound to limit the flexibility of my capacity to have total free rein over how the project I first imagined could be physically created, and I assigned myself a set of objectives without knowing what tools I would be using to try to carry them out, making it very difficult to accurately imagine the problems that would manifest themselves along the road to completion. Fortunately however, once the foundational basis of research and annotation was complete, I had the bulk of the information necessary for assembling a useful archive surrounding the works of Whitman and Hughes, in addition to producing my own critical commentary to synthesise a more effective reading of the two. The only factor left to-be-determined then was the presentation and ergonomic experience of accessing this information, and how it might best be aesthetically formatted to be most conducive to study of Langston Hughes’ poetry, and tracing the line of his literary heritage back to the handful of Whitman’s key most influential poems from his 1860 Leaves of Grass.

Overview of Project’s Achievements:

I think this image of the internal workings of my project’s program shows aptly the extent to which I have managed to highlight the intertextuality and overarching themes that unite the poem’s selected from the works of Langston Hughes, with a particular view towards his personal and literary relationship with the father of American poetry, Walt Whitman, whose first major published collection Leaves of Grass preceded Hughes’ by almost exactly one century.

As it stands, my current published project successfully achieves what it set out to do. The textual document is performative and interactive, allowing readers and scholars to engage critically and actively with the text, following specific threads of thought, theme, and technique to discover a variety of perspectives on the comparative works of these two poets in dialogue. This is likewise one of the central accomplishments of this piece, in that it allows for a guided reading experience directly from one poet, Hughes, to the his predecessor Whitman, allowing any curious reader a glimpse into the poetic developments and processes of Hughes as he composed his own literary legacy.

The crucial technique of adding hyperlinks and colour-coded highlights to individual words that the Twine program affords, and the creation of a series of linked pages offering multiple layers of new information was also immensely useful for enabling me to track the thematic and verbal preoccupations and influences of Langston Hughes on a line-by-line basis. Similarly, the efficiency of highlighting several key words or phrases across the course of one or more poems, and linking them to a unified separate page discussing the emblematic theme or source material to which they can be linked was crucial for establishing the holistic basis of delving into Langston Hughes’ poetic works.

Another area that I touched upon in my initial proposal was the compilation of critical commentaries and the wealth of extant scholarship on Langston Hughes, and his relationship to Walt Whitman. Ed Folsom’s essay, ‘So Long, So Long! Whitman, Hughes, and the Art of Longing’ in Walt Whitman, Where the Future Becomes Present (2008) was far and away the most useful resource in this regard, spanning a breadth of works by each poet and elaborating on their common historical contexts and literary developments. This pivotal essay became the focal point of my initial structuring of the project, as it directed me towards which central poems I should select as the basis of my investigative research. It is also an incredibly well sourced essay for such a short piece, and directed me towards several other leading scholars who have discussed not merely one or the other of Langston Hughes or Walt Whitman, but specifically the interaction and overlap of the oeuvres of both poets; the most notable of which being George B. Hutchinson. However, from this I even still pushed myself to track down more academic perspectives on Hughes’ poetry in particular, as a tool for fleshing out the varying interpretations of his extensive body of poetry. I think my project is all the richer for this additional resource, and its primary strength as a digital humanities project lies in the new collation and examination of material that is too often viewed as disparate fields of enquiry: either Whitman, or Hughes, but too rarely both together, and too rarely coupled with detailed annotated responses and historical contextualisation of these landmark works in modern American literature.

Areas for Extension

When handling the works of poets as prolific as Whitman and Hughes, the most difficult decisions to negotiate are always the editorial ones: which poems to include, which to refer to in passing, and which to delve into in detailed line-by-line depth. Consequently, I would say that if this project were to continue being added to and compiled, the primary area for extension would be that of its scope. Hypothetically, this project could have encompassed and broken down every single poem included in Langston Hughes’ 1959 Selected Poems publication. The only limiting factor was the timescale of this course and the academic semester, and also the unwieldy bulk of information that would have followed, as I tracked down the countless allusions made by Hughes, and made to Hughes in contemporary scholarship.

In curating the focus of this digital humanities project however, I decided that consistency was the crucial factor here for efficacy and ease of use. It would not do to delve into one poem in drastically greater depth than another; nor would it be appropriate to unbalance the project by approaching it clumsily from two conflicting perspectives. This is why I chose in this preliminary version to centre the works of Langston Hughes, rather than paying completely equal regard to both Hughes and Walt Whitman from the entry window of the Table of Contents, as I had first thought to when I initially conceived of the project. Given how truly vast Whitman’s poetry is, all too soon it became abundantly clear that if I were to attempt a word-by-word breakdown of his poetry in linking it to Langston Hughes’ own as a secondary perspective, I would not only be working right the way to the start of next year, but above all I would be grasping at straws, and treating the poetry anachronistically. Obviously, not every Whitmanian image can be thought of in connection to Hughes, as Whitman lived several decades before Hughes was even born. This made Langston Hughes the much more intuitive starting point, not only as a researcher, but as a reader accessing the information compiled within the project.

That said, I think the next step for this piece would be to take the Whitman poems that Hughes explicitly references in his own, and provide a complimentary pathway through the digital project that allows you to start from either perspective. The completion of an accompanying Whitman half to the project was beyond by reach of feasibility, but would be the final piece that would truly place the two in direct dialogue with one another, as Hughes had intended. This could moreover be supplemented with extra selections from the 1860 edition of Leaves of Grass that thematically compliment the preoccupations of both Whitman and Hughes in literary and historical terms, even if they do not directly correspond to a particular allusion made by Hughes; for example, I Sing the Body Electric. However, given the circumstances, I think my approach of a literary journey back through time is the most lucid for use in a prototype digital archive of this nature.

Project Shortcomings

The primary shortcoming I encountered in the production of this online resource was that it was perhaps in some ways too effective at targeting one of its earlier elaborated goals: the line-by-line analysis and annotation of poems. While the program that I ended up using was very well suited to such breakaway commentaries and developing offshoot trains of critical thought, it was much more difficult then to redirect the avenues of investigation towards the overarching structural parallels shared by both Whitman and Hughes as they oversaw the publication of their collected bodies of poetry, in 1860 and 1959 respectively. As I identified in my initial project proposal, both Whitman and Hughes are distinct for their employment of thematic clusters of poems, which are grouped in such a way as to evoke clear moods, tones, and images that resonate uniquely with the transcendent concerns of their poetry. My best effort to acknowledge this can be seen by following the pathways of “Montage of a Dream Deferred”, and “Words Like Freedom” – here, I created pages dedicated to examining the implications of these titles, and how they find their basis in the same Whitmanian cluster technique I have just described. The ability to truly compare the structural basis and how this reflects the concerns of each poet respectively remains elusive; probably because this requires a broader approach to reading than a close-analysis document can provide.

Moreover, in some ways the structural limitations of the Twine software itself could also be pinpointed as areas that would warrant fine-tuning if this project were to be continued or expanded. For instance, the limited options available in colour-coding, which I partially chose to keep as such in an allusion to the American flag and thematic mood of the poetry displayed, could certainly benefit from an expansion of options. There should be a better way of clarifying where any particular hyperlink might lead; and the project would most certainly benefit from improved navigational tools such that readers have greater flexibility in accessing the information and knowing how to move through the series of compiled and curated texts presented through the platform.

For example, when testing the project with peers within this course, it often took some time before new users identified the Forward and Backward arrows that seem to be camouflaged in the top left. Had I possessed the technical wherewithal to adjust these and render them more visible, I certainly would have done so. I think the solution would be the addition of something like a tool bar or control panel that remains constantly accessible to users of the page, such that more calculated leaps and revisitations to particular sources of material throughout the database could be made according to the particular needs of the individual reader.

Potential Reimaginations

In my mind, in order to hypothetically take this project to the next stage of its overall development, would require two steps. The first, as outlined above, would be the full extension of its content material, to encompass the vast swathes of published works that Langston Hughes and Walt Whitman produced over the course of their respective lifetimes. This alone would require a monumental amount of effort; but the results would certainly be unparalleled for their use in illuminating this avenue of the development of American literary culture, as the course of history forged its path towards the pinnacle of the Harlem Renaissance of which Langston Hughes was one of the foremost pioneers. With this accumulation of content however, or perhaps even before it would necessarily come a total overhaul of the platform technology, both from the point of view of the researcher/archivist, and equally from that of the online user and prospective reader of the works of Hughes and Whitman in dialogue.

The only way of achieving this that I can bring to mind would be the creation of a custom-built, standalone website whose layout and functionality was programmed specifically to maximise the ease of accessibility of this compiled treasure trove of literary information. The example that comes to mind as the basis for such an enterprise is the online Walt Whitman Archive, which in fact I relied upon heavily over the course of my research for the production of this project, as it is one of the easiest to use and most reliable repositories of the earlier published editions of Walt Whitman’s poetry, which was essential in examining the two poets for their historical significance and relationship: both poised a century apart, both in times in American history that lie on the brink of national turmoil and civil unrest. The website would be able to effectively host the database of poems, with increased capacity for adding marginalia and cutaways, or dialogue boxes that allow for the multiple layers of research, and thus a fusion of the two distinct diegetic levels of source material and subsequent inspiration, which should truly realise the goal of creating a coherent, overlapping narrative with the two writers and their works in dialogue.

A custom-built platform of this kind would also enable the expansion of the kind of content that could be included in the database. For instance, Twine was significantly limiting in that it could only contain textual information – no pictures, music, or audio-visual enhancements of any kind were supported in the software’s codebase. With a transition into a new platform, the possibility for a full multimedia exploration of the lives and works of Hughes and Whitman opens itself up within reach; from where they lived and worked, to the travels they undertook, and the iconic images that found their way into the language of their poems. The possibilities for compiling relevant archival materials are truly endless – and in my mind, the ideal end result would almost resemble an online museum exhibition of the two poets; transcending not only the century of time between them, and the unjust shortcomings of the United States in their respective lifetimes; but also, all physical constraints on their poetry and output, that might have ever limited their readership and appreciation in the annals of American cultural history.

Mikayla’s Reflection

The True Story of Uncle Tom

By Mikayla Harris

One day, Julia went on a walk with her Grandmom. It was a nice, sunny day and it was perfect for a walk in the woods. After they had walked for a bit, Grandmom stopped and sat down. She needed to rest.

“Julia,” Grandmom asked, “Do you know the Pledge of Allegiance?”

“Yes! We say it every day in school.”

Julia stood in front of her Grandmom, put her right hand over her heart and said:

“I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the United States of America and to the Republic for which it stands, one nation, under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

“Very good, darling” Grandmom said. “But Julia, did you know that America did not always have liberty and justice for all?”

“What do you mean?” Julia asked.

“Well, people with dark skin—people who looked like us—had to work for many hours every day in cotton fields and they were not paid anything for their work. They were called slaves.”

“We learned about slaves in school,” Julia said. “It made me sad.”

“It was a sad time for the slaves. And slavery went on for many years. Hundreds of years.”

“How did it end?” Julia asked.

“It ended during the American Civil War. The North and the South fought each other. The North won and President Abraham Lincoln freed all the slaves.”

“President Lincoln sounds like a good man.”

Grandmom chuckled. “Yes, he was. But he didn’t do it alone. He had help from free black people and from white people too. Have you ever heard of Harriet Beecher Stowe?”

Julia shook her head no.

“Ms. Stowe wrote a book that many people said helped end slavery because she showed black people were human beings just like the white people.”

“What was the book called?” Julia asked.

“Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

Julia frowned. “But Daddy told me ‘Uncle Tom’ is a mean word,” said Julia.

“Yes. Nobody likes to be called an Uncle Tom today.”

“Why not?” Julia asked.

“Because today people think it means a black person who will do anything to be liked by white people.”

“But why would you not want to be liked by white people? Doesn’t everyone want to be liked by everyone?”

“Yes, everyone does. But people say that Uncle Toms want to be liked by white people who are mean to black people. They say that is what Uncle Tom did in the book. People don’t like Uncle Tom because they say he was too obedient when he shouldn’t have been,” Grandmom said.

“But,” Grandmom said, “that is not what Ms. Stowe meant when she wrote about Uncle Tom. She wanted to make him a person that was so good and so kind that it would inspire everyone to try to be like him. In the book, Uncle Tom is caring, considerate, and he loves all people—black or white.”

“So why would people not want to be an Uncle Tom then?”

“Because after the novel came out, people who did not want slavery to end made fun of Uncle Tom. They put on plays where they made him thin, old, and weak. They made him look like a silly man who never stood up for himself. They said that Uncle Tom liked being a slave.”

Grandmom stood up and started walking again. “But that was not true. In the book, Tom was actually a very strong man. And he was good. Uncle Tom was a good man. Just because he liked his slavemaster’s family did not mean he liked slavery itself. He saved a little girl from drowning. He listened to people when they needed someone to talk to. In the end, he even forgave his evil slave master for hitting him.”

“Why did he do that?” Julia asked.

“Because forgiveness is the best gift a person can give. We all need to forgive, even when people are being mean to us. That ability to forgive is what made Uncle Tom a hero.”

“So people should want to be an ‘Uncle Tom’ then, Grandmom?” said Julia.

“Yes, because the real Uncle Tom, the one not made up by bad stories, loved all people, whatever color they were.”

“I’m going to do that.” The light was fading, so the two turned to walk back home.

“You should, my sweet girl,” Grandmom said as she stroked Julia’s hair, “we all should.”

Reflection

When I was five years old, I was obsessed with Shirley Temple. I watched all her movies, and while I watched I stood in front of the television and fastidiously tried to learn her dance moves. To this day, the area of carpet directly in front of the television is more worn than the rest of the carpet in my family’s living room. Whenever my family went out to eat, I always ordered a Shirley Temple (a non-alcoholic drink made with Sprite, grenadine, and topped with a maraschino cherry). Although Temple’s infamous ringlets were red, I structured my curls to mimic hers. My parents indulged me as they loved to watch me tap dance around the house. They bought me every Temple movie available on VHS and smiled at my gleeful reaction as I ran to play each new tape.

One typical Saturday, I was dancing along to a newly-acquired Temple movie. My Dad came downstairs and stood watching me for a minute, laughing at my spastic movements. Then he turned to look at the movie more closely. As he continued to watch, his eyebrows furrowed in confusion. His confusion quickly turned to anger.

“Turn it off,” he said. I continued dancing.

“Turn it off,” he repeated. I kept dancing.

“Why, Daddy?” I asked.

“Mikayla,” he said sternly, “I am not going to tell you again. Turn that off.”

“But I’m watching it!”

“Well you can’t watch it anymore,” he responded, his voice starting to rise.

My Mom, hearing the loud voices, came in to the living room.

“What’s going on?” she asked.

“She needs to turn that movie off. Now,” my Dad said to her.

“Why? What’s wrong with it?” my Mom pressed.

“Just look at it.”

My Mom stood and watched the movie for a few moments. Her eyebrows furrowed in similar confusion to my Dad’s. But her expression did not turn to anger. She turned to my Dad.

“I don’t get it,” she said, “what’s wrong?”

My Dad looked at her with a hurt look that I had never seen cross his face before. He shook his head.

“I’ll explain later,” he said. “Just trust me on this, alright?”

He ejected the tape from the player and walked upstairs. I never saw it again.

***

I did not think anything about that incident until I started working on this paper. I did not understand why my Dad got so upset about the movie, and he never explained his reaction to me. When I started my project, I began with a search in to the Uncle Tom stereotype and the proliferation of it throughout popular culture. I quickly learned that the Uncle Tom Harriet Beecher Stowe described in Uncle Tom’s Cabin radically differs from the “Uncle Tom” known to most today. The Merriam Webster dictionary defines “Uncle Tom” as “a black who is overeager to win the approval of whites (as by obsequious behavior or uncritical acceptance of white values and goals); a member of a low-status group who is overly subservient to or cooperative with authority” (Merriam-Webster online dictionary, n.d.). The protagonist of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, however, is not like this. He is not “overly subservient” to whites. He willingly sacrifices himself and his well-being to help others, white or black.

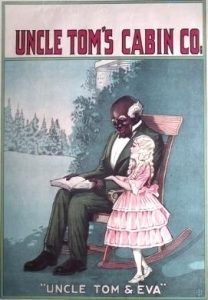

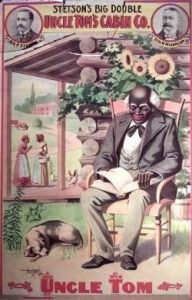

Yet negative images associated with “Uncle Tom” flourished in the post-war years. These images came from minstrel shows of white men playing Uncle Tom in blackface as a fool or an apologist for slavery (Stowe Center, UTC and American Culture). Stowe described Uncle Tom as a strong, muscular man, but the productions showcased Uncle Tom as a weak, old man with grey hair, a receding hairline, and a cane. These “Tom Shows” as they were called denied Uncle Tom the agency he had in the book as a powerful individual who could fight for resistance. Professional “Tom Shows” toured annually for about ninety years following the book’s publication in 1852 and some versions were filmed for movies and cartoons.

“Tom Shows” put Uncle Tom’s Cabin in to the popular imagination in a way that infantilized and trivialized the slave experience. Images of a happy, submissive older black man flooded twentieth-century cultural forms, including Shirley Temple movies. As I researched for this project, I came across information about Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, an actor in many Shirley Temple movies. Robinson was an older black man who often tap danced alongside Temple. Their relationship mirrors the one between Uncle Tom and Eva in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The 1935 Shirley Temple movie The Little Colonel features a big dance number. Temple is the star of the number and Robinson supports her as Temple’s backup dancer. The film showcases the narrative of an older, subservient black man happily deferring to the needs of a privileged white child.

The Little Colonel, as it turns out, is the movie my Dad stumbled upon me watching all those years ago. His angry reaction to the film came from seeing yet another image of an “Uncle Tom” playing out in front of him. He did not want to see a negative depiction of a black man on the television in his home and he did not want his impressionable daughter seeing the image as well. My Mom did not initially understand my Dad’s issue with the film. My Mom is white and my Dad is black. She was not aware of the “Uncle Tom” stereotype and the issues my father had with it. I was little and did not understand what was going on. But now that I know about the stereotype and the images associated with it, I see how pervasive they are in our national culture.

***

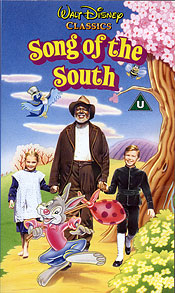

Most of the rides at Disney World are based off a popular Disney movie—the Dumbo ride from the movie of the same title, the Buzz Lightyear Adventure from Toy Story, and Star Tours from Star Wars. But the origins of one of Disney World’s most popular rides, Splash Mountain, remain unknown to most Americans. Splash Mountain has always been my favorite ride. It is a log water attraction with outdoor and dark interior portions culminating in a fifty-foot drop into cold water. Splash Mountain tours riders through three adventures of Brer Rabbit, a cunning trickster who uses his wit to escape his enemies, Brer Fox and Brer Bear. In the first adventure, Brer Rabbit craftily dodges a snare trap and uses it to trap Brer Bear instead. The log ride continues as Brer Rabbit finds his “laughing place”, closely followed by Brer Fox and Brer Bear. Instead of leading them to this fictitious spot, however, Brer Rabbit leads his adversaries into a beehive. In the third and final scenario, Brer Fox finally captures Brer Rabbit and plans to roast him. Using reverse logic, Brer Rabbit convinces Brer Fox to throw him into the briar patch (mimicked in the ride by the legendary fifty-foot drop). Brer Rabbit and the riders escape unscathed (save for some wet clothing) as Brer Rabbit exclaims, “I was born and raised in the briar patch!”

Few of the attraction’s riders know the basis of the ride’s story and characters and its complicated racial past. I wrote about this complicated past in a final paper for a history seminar I took in the fall of 2015 titled “Problems with American Historical Memory: The Civil War”. Splash Mountain is modeled after Disney’s 1946 hybrid live action and animated film Song of the South, which is based on Joel Chandler Harris’s Uncle Remus and Brer Rabbit stories. The film also features the familiar Disney ditty “Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah”, sung by James Baskett. Baskett played the film’s protagonist, Uncle Remus, a black former slave living and working on a plantation in Georgia. After several reissues, the film disappeared from circulation after its 1986 release because of its racial controversy. Today, the Disney Corporation markets only the non-racialized portions of the film, such as “Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah” and Splash Mountain rather than the negative depictions and stereotypes demonstrated by the Uncle Remus character.

Disney disguises the racial undertone of Song of the South, but doing so perpetuates the power we grant stereotypes. Rather than try to understand where a stereotype may come from and fight against it, we either accept it or we try to push it from the public discourse. My Dad did this when he told me to turn off The Little Colonel rather than teach me about the issues he had with it. If we do not learn from stereotypes, we can never seek to correct them.

Walter Lippmann, an American writer and political commentator, coined the term “stereotype” in popular discourse in his 1922 book Public Opinion. Stereotypes, he writes, provide a distorted mental picture of reality because “we are told about the world before we see it” (Soares, 51). “For the most part,” Lippmann writes, “we do not see and then define; we define first and then see. In the great blooming of the outer world we pick up what our culture has already defined for us, and we tend to perceive that which we have picked out in the form stereotyped for us by our culture,” (Soares 51). Cognitively, it is easy for us to accept a stereotype because it is a way of seeing the world that “our culture has already defined for us”. We learn stereotypes at a young age and they then influence how we see the world. Children “pick up” stereotypes and are often just told that these stereotypes are “bad” without learning why. They deserve to know the why, which is what I sought to do in my final project.

***

The first recorded instance of use of the term “Uncle Tom” as a derogatory slur was in a 1919 speech made by political leader Marcus Garvey to a crowd of black Americans. “From 1914 to 1918,” he said, “two million Negroes Fought in Europe for a thing foreign to themselves—Democracy. Now they must fight for themselves. The time for cowardice is past. The old-time Negro has gone—buried with ‘Uncle Tom.’” (Garvey, The Afro-American). The term “Uncle Tom” is often used within the black community to critique the behavior of a black person in relation to the white race. A. Philip Randolph popularized the term in his advocacy for the creation of a union for Pullman Porters. He created the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters to support the workers’ rights and lambasted the black workers who did not join the union. In a 1925 political pamphlet he wrote, “The handicap under which the porters are now laboring are due to the fact that there are too many Uncle toms in the service. With their slave psychology they bow and kowtow and lick the boots of the Company officials, who either pity or despise them” (Randolph, The Messenger).

The image of an Uncle Tom as a weak, submissive figure stems from the “Tom Shows” performed to American audiences across the country. This Uncle Tom is not, however, the one Stowe wrote in her book. Stowe employs Christianity in her abolitionist narrative for Uncle Tom’s Cabin. In so doing, she makes Uncle Tom a Jesus-like martyr figure. Uncle Tom dies because his master, Simon Legree, beats him to death after Uncle Tom refuses to betray the whereabouts of two female slave runaways. His passivity is thus a character strength, not a weakness. He does not “bow and kowtow and lick the boots” of his master. Instead, in the ultimate test, he protects his race.

Stowe glorifies Uncle Tom as the ultimate hero of the novel and champions his behavior as a model of behavior for all people, regardless of race. Uncle Tom is self-sacrificing because of the love and respect he feels for the people around him. It was radical for Stowe to equate a black character to Jesus. “Tom Shows” were white Americans’ attempts to undercut the social validity Stowe gave Uncle Tom. But in the novel, Uncle Tom is the redeemer. His name should not be the one with negative connotations. If any name should be a derogatory term, it should be Simon Legree.

***

The original conception for my final project was to provide a space for teaching the truth of Uncle Tom’s Cabin to a young audience. Children are impressionable and subject to quickly adopt any observed stereotypes. As a child I did not know what was wrong with The Little Colonel, but in recent years I learned about the negative imaging of older black male figures such as Bojangles Robinson. Additionally, I enjoyed Splash Mountain for many years without any knowledge of the movie behind it. I wanted my project to be an intervention into a popular culture where negative imagery of “Uncle Toms” surrounds us, perhaps in an even more pervasive form than we recognize.

I initially struggled to find a “voice” for writing this children’s book. I only started to take creative writing courses at Yale in my sophomore year when I took Daily Themes. Following that course, I took Playwriting and Screenwriting. Writing for children, however, is markedly different from these other writing forms. In Playwriting and Screenwriting we learned about writing in voices separate from our own, but even in those courses I created characters somewhat like me. Both my play and screenplay covered the lives of high school and college-aged individuals, so the dialogue I created mirrored that of the people around me. As a college student, however, I do not spend much time with children so writing in a language understandable to them proved difficult.

I turned to contemporary children’s books to aid in my pursuit of finding a narrative language. Some of these books were: Where the Wild Things Are, Goodnight Moon, and Blueberries for Sal. Ultimately, I decided that my target audience would be children aged 6-8. I figured this would be an age demographic that had some knowledge about what slavery was. It was also particularly important for me to find books specifically written for black children, such as Happy to be Nappy and If I Ran for President, since I planned to write my children’s book with a black audience in mind. I wanted my children’s book to be a celebration of Uncle Tom rather than a criticism of Stowe and the negative images associated with the notion of an “Uncle Tom” today.

Children’s stories often have a very clear moral. For my children’s book, The True Story of Uncle Tom, I wanted to streamline the moral Stowe laid out in her novel to make it even more explicit. Stowe grounds her case for abolition in Christianity. She makes Uncle Tom a Jesus-like figure who in the end shows everyone the importance of forgiveness. As Uncle Tom is being beaten to death, he opens his eyes and looks at Legree and says, “Ye poor miserable creature! There ain’t no more that ye can do! I forgive ye, with all my soul.” In Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Stowe created fully developed black characters. She made the slaves humans rather than property to show people the immorality of slavery. The ability to forgive is crucial in Stowe’s story as she shows that it is a characteristic that transcends race. In making Uncle Tom the hero of the story, Stowe shows that he is a human everyone should respect and admire rather than a slave who can be subjected to mistreatment and humiliation.

***

The main limitation of my children’s story is my inability to produce illustrations. I consider myself a creative person, but not when it comes to the visual arts. Last year, I took a seminar called “Mastering the Art of Watercolor”. The Professor was nice and helpful, but he eventually encouraged me to develop more “abstract” and “modern” art since my attempts at any literal depictions of Yale University’s gothic architecture failed. Illustrations are essential components to children’s books as they give children visuals to aid in their understanding of the words on the page. They make the story fun and beautiful in a way lost in adult novels. If I were to try to publish my book, or to pursue the craft of writing for children, I would find a collaborator to create my illustrations. Most children’s books are collaborations between an author and an illustrator. I would look forward to working with an artistic partner to create a balance of words and pictures appealing to a young eye.

As a child, my favorite time of day was when my Mom would come and read to me before bed. She read simply, without crazy voices or anything of that sort, but something about the soothing sound of her voice lulled me to sleep. When I worked as an assistant teacher at a kid’s camp a few years ago, we spent an hour every day reading to the children. Children learn to read and, at least in my experience, learn to love to read through hearing books read out loud to them. To this day, I love to listen to audiobooks because I think the addition of a human voice to a story adds a layer of depth inaccessible by the simple written word. That is why I decided to provide an audio recording of myself reading The True Story of Uncle Tom. I think my narration supplements the story and adds to the experience of understanding the tale.

If I had full time and resources, I would make an animated movie of The True Story of Uncle Tom. To this day, I love animated films. I think they are a great source of entertainment for children and adults alike. My dream job would be to write a Disney movie as I believe I have a very childlike sense of humor. Maybe that will be something I pursue, and The True Story of Uncle Tom would have just been the start. We’ll see what comes next…

Below are some images that guided me through my research. I would provide these images to an artist as inspiration for a collaborative illustrated book of The True Story of Uncle Tom.

Harry Birdoff Collection, Harriet Beecher Stowe Center. “I Is Uncle Tom. I Won’t Hurt You”. Color lithograph poster for stage production. http://utc.iath.virginia.edu/saxon/servlet/SaxonServlet?source=utc/xml/media/onstage-images/ostspostrs.xml&style=utc/xsl/utcprint.xsl&print=yes.

Harry Birdoff Collection, Harriet Beecher Stowe Center. “Uncle Tom and Eva”. Color lithograph poster for stage production. http://utc.iath.virginia.edu/saxon/servlet/SaxonServlet?source=utc/xml/media/onstage-images/ostspostrs.xml&style=utc/xsl/utcprint.xsl&print=yes.

Harry Birdoff Collection, Harriet Beecher Stowe Center. “Uncle Tom”. Color lithograph poster for stage production. http://utc.iath.virginia.edu/saxon/servlet/SaxonServlet?source=utc/xml/media/onstage-images/ostspostrs.xml&style=utc/xsl/utcprint.xsl&print=yes.

Disney Corporation. Song of the South. Cover Art. http://www.snopes.com/disney/films/sots.asp.

Disney Corporation. Song of the South. Uncle Remus and the Kids. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Song_of_the_South#/media/File:Remuskids.jpg.

Fox Film. The Little Colonel. Shirley Temple and Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. Released February 22, 1935. http://black-face.com/Bill-Bojangles-Robinson.htm.

Encyclopedia Britannica. “Bill Robinson”. Published March 3, 2017. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Bill-Robinson.

Work Cited

Garvey, Marcus. “Garvey Urges Organization”. The Afro-American. Baltimore: 28 February 1919. Accessed 29 April 2017. http://utc.iath.virginia.edu/africam/afar93at.html.

Harriet Beecher Stowe Center. “Uncle Tom’s Cabin and American Culture”. 2015. Accessed 27 April 2017. https://www.harrietbeecherstowecenter.org/utc/american_culture.shtml.

Randolph, A. Philip. “Pullman Porters Need Own Union”. New York: August 1925. Accessed 29 April 2017. http://utc.iath.virginia.edu/africam/afes92at.html.

Soares, Isanilda. “Racial Stereotypes in Fictions of Slavery: Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe and O Escravo by José Evaristo D’ Almeida”. Dissertation for the Universidade de Coimbra, 2013.

“Uncle Tom.” Merriam-Webster.com. Merriam-Webster, n.d. Web. 2 May 2017.

Ethel Waters and Topsy: Say WHAT?

I spent some time researching artists that arose from Topsy’s influence on black entertainment. I was struck by the similarities between the upbringing of Ethel Waters and Topsy. In her autobiography, Ms. Waters talks about growing up, saying, “I never was a child. I never was coddled, or liked, or understood by my family. I never felt I belonged. I was always an outsider.” The same loneliness seemed to run like a thread through Topsy’s story, but there’s more! Ethel Waters did not have a relationship with either parents, and lived with her alcoholic aunts. From them, she learned to tell a story through song. Later, living with her sisters, she witnessed quite a few heavy moments, all of which required her to grow up quickly. Ethel, having endured much trauma, was able to keep her head on straight working as a chambermaid. There isn’t an exact alignment in stories here, but keep reading.

In a 1927 film version of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, there was a deleted scene in which Topsy was in Miss Ophelia’s room, putting on “white face”. Why the scene was removed, is unclear, BUT, it is striking in it’s presentation of Topsy. I haven’t seen such a deliberately ugly character since Nanny McPhee. I was appalled at her hair, clownish facial expressions, grotesque features (my doll will be nothing of the sort)… In the scene, Topsy is putting white powder on her face, taking delight in her new (whitened) image. Miss Ophelia walks in and catches Topsy playing. She looks up sheepishly and the following words stretch across the screen, “Please, Miss Feely, I jes’ wanted to make myself white — so I could be good like Missy Eva.”

THIS scene mirrors another scene coming straight from Stowe’s pen: “On one occasion, Miss Ophelia found Topsy with her very best scarlet India Canton crape shawl wound round her head for a turban, going on with her rehearsals before the glass in great style (212)

BUT, here’s the more part: Ethel Waters wrote about the same moment in the mirror in her autobiography, Eye is on the Sparrow, “I had the most fun at the Harrod Apartments, on the days when I substituted for one of the chambermaids. I was allotted half an hour to make up each room but soon became so efficient that I could finish the work in ten minutes. Then I’d lock the door, stand in front of the mirror and transform myself into Ethel Waters, the great actress.”

Jayna Brown describes this sort of moment by saying of Topsy, “Topsy casts off the domestic harness and transforms herself in the space of labor, reclaims her body in the place of work.” In the same the way, Ethel Waters is reclaiming her body by creating a character for herself in a place were she labors with no face, with little sense of self. This reminds me of a previously posted picture of Kara Walker’s reimagining of Topsy holding a watermelon, looking like an angel.

What I’m trying to get at is quite obvious but shouldn’t go without being said. The power of visual representations has been evident in every facet of my research. Makes sense, I guess. Sight allows us to visually connect with everything around us. It is the key to the worlds we inhabit, real and imagined. Therefore, what we see dictates how we feel, what we believe, creates memories, impression….

I want this doll that I be representative of what Topsy would have seen in her “Ethel Waters mirror moment”- someone beautiful, confident, and free. It’s funny to think that in the mirror, even when you are playing, what you see is yourself. Even if it’s a different self, it is still the self. Everything you want to be, you already are but I digress.

Topsy’s doll will be a realization of the self she was never allowed to be unless she was pretending. That’s also a funny thought because throughout much of the book she is doing just that, pretending. Ethel Waters went through the same emotions, but she had her moment to shine. This doll is my attempt to create Topsy’s diva persona. Maybe then she’ll have a shot at a career like Ethel’s . Her debut will be as a lovable little doll that’s hugged and tucked in at night. In her mansion, she’ll have drawers full of clothes, a piano to write songs, and other little chocolate girls that comment on how nice her hair looks. I hate that this was not her reality- that in the world of the novel she has none of this From people like Ethel Waters, folks who lived a life just like Topsy, we do find triumph. That gives me some hope.

Ethel Water is to Topsy as Diva is to Doll.

But What of Her Body

Topsy has had quite the afterlife. Beyond the page, she was consumed on a mass scale by white audiences, performed by both white (in blackface) and black artists such as Ida Forsyne, and is credited with inspiring black artistry especially that associated with body movements.

A scholar, Jayna Jennifer Brown, commented on Topsy, saying, “Topsy is framed and developed in the novel as a transnational figure for the heathen native. This was part of the reason why the English responded so readily to the character.” (Topsy became a national traveling act during the Vaudeville period) One might even conclude that the bathing of Topsy when she arrived into the hands of Miss Ophelia, was her Baptism of sorts, an initiation into a devout existence of reform, English academics, and subservience.Stowe presents her Western readership with Topsy, a primitive, uncivilized being described as, “goblin-like” and “heathenish”. (UTC 202)

It is during this bathing that we are introduced to Topsy’s body as an object of historic and consistent abuse. Permanent marks are left from years of beatings, scarred skin, a darkened surface….

Topsy is a child- to be so young with so much trauma. That’s not a trope. It is true of so many childhoods of the time, and quite honestly, still remains true of children around the world today.

Anyway, what are we take make of this little girl’s body? It isn’t smooth and white as one might imagine Eva’s body, but disfigured and marked up like property. I would like to explore whether or not that has anything to do with her being regarded as heathen. If her body was unscarred, her hair of a different texture, her presentation a little cleaner, would she be worthy of less pity and more relatability? Even more than her physical appearance, I wanted to consider her performance via her body. There is a long history of blacks using their bodies as a way to redefine their freedom- to escape and defy. Does Stowe’s presentation of Topsy fit this framework? What of Topsy’s body? Is she free?

Two modes of thought have grown from her character:

- Topsy is an embarrassment to a black race that is trying to overcome comic mockery of cultural habits. New freedoms brought a desire for a new image- an image that reflected greater dignity. Topsy’s lasting cultural impact, was a disgrace to that hope. In a 1935 article, Montgomery Gregory put it this way, “Although Uncle Tom’s Cabin passed into obscurity, Topsy, survived. She was blissfully ignorant of any ancestors, but she has given us a fearful progeny. The earliest expression of Topsy’s baneful influence is to be found in the minstrels…these comedians, made up into grotesque caricatures of the Negro race, fixed in the public taste a dramatic stereotype of the race that has been almost fatal to a sincere and authentic Negro drama.”

Those are some pretty harsh words for a character that isn’t even living. What I can’t understand is why Topsy is to blame. There were many a black artist (REAL, living, breathing black artists) who played into the same minstrel stereotype that was just as detrimental to the black image. Topsy represented a black youth who had no history to claim (father, mother, home) and little regard for respectable decorum. That was part of her freedom. Her performance was one of physical and mental survival…

- Topsy’s character performance is one of freedom. Perhaps, you could look at her like a farce, but one must also consider her ability to remain unmoved by any punishment forced upon her. Her impenetrableness to pain indicates, “her body is resistant to violent claims of ownership. “- Jayna Brown

Her every movement, joke, theft, song, and facial expression makes manifest her authority over herself. Individual gestures of any nature can neither be bought nor sold.