The True Story of Uncle Tom

By Mikayla Harris

One day, Julia went on a walk with her Grandmom. It was a nice, sunny day and it was perfect for a walk in the woods. After they had walked for a bit, Grandmom stopped and sat down. She needed to rest.

“Julia,” Grandmom asked, “Do you know the Pledge of Allegiance?”

“Yes! We say it every day in school.”

Julia stood in front of her Grandmom, put her right hand over her heart and said:

“I pledge allegiance to the Flag of the United States of America and to the Republic for which it stands, one nation, under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.”

“Very good, darling” Grandmom said. “But Julia, did you know that America did not always have liberty and justice for all?”

“What do you mean?” Julia asked.

“Well, people with dark skin—people who looked like us—had to work for many hours every day in cotton fields and they were not paid anything for their work. They were called slaves.”

“We learned about slaves in school,” Julia said. “It made me sad.”

“It was a sad time for the slaves. And slavery went on for many years. Hundreds of years.”

“How did it end?” Julia asked.

“It ended during the American Civil War. The North and the South fought each other. The North won and President Abraham Lincoln freed all the slaves.”

“President Lincoln sounds like a good man.”

Grandmom chuckled. “Yes, he was. But he didn’t do it alone. He had help from free black people and from white people too. Have you ever heard of Harriet Beecher Stowe?”

Julia shook her head no.

“Ms. Stowe wrote a book that many people said helped end slavery because she showed black people were human beings just like the white people.”

“What was the book called?” Julia asked.

“Uncle Tom’s Cabin.”

Julia frowned. “But Daddy told me ‘Uncle Tom’ is a mean word,” said Julia.

“Yes. Nobody likes to be called an Uncle Tom today.”

“Why not?” Julia asked.

“Because today people think it means a black person who will do anything to be liked by white people.”

“But why would you not want to be liked by white people? Doesn’t everyone want to be liked by everyone?”

“Yes, everyone does. But people say that Uncle Toms want to be liked by white people who are mean to black people. They say that is what Uncle Tom did in the book. People don’t like Uncle Tom because they say he was too obedient when he shouldn’t have been,” Grandmom said.

“But,” Grandmom said, “that is not what Ms. Stowe meant when she wrote about Uncle Tom. She wanted to make him a person that was so good and so kind that it would inspire everyone to try to be like him. In the book, Uncle Tom is caring, considerate, and he loves all people—black or white.”

“So why would people not want to be an Uncle Tom then?”

“Because after the novel came out, people who did not want slavery to end made fun of Uncle Tom. They put on plays where they made him thin, old, and weak. They made him look like a silly man who never stood up for himself. They said that Uncle Tom liked being a slave.”

Grandmom stood up and started walking again. “But that was not true. In the book, Tom was actually a very strong man. And he was good. Uncle Tom was a good man. Just because he liked his slavemaster’s family did not mean he liked slavery itself. He saved a little girl from drowning. He listened to people when they needed someone to talk to. In the end, he even forgave his evil slave master for hitting him.”

“Why did he do that?” Julia asked.

“Because forgiveness is the best gift a person can give. We all need to forgive, even when people are being mean to us. That ability to forgive is what made Uncle Tom a hero.”

“So people should want to be an ‘Uncle Tom’ then, Grandmom?” said Julia.

“Yes, because the real Uncle Tom, the one not made up by bad stories, loved all people, whatever color they were.”

“I’m going to do that.” The light was fading, so the two turned to walk back home.

“You should, my sweet girl,” Grandmom said as she stroked Julia’s hair, “we all should.”

Reflection

When I was five years old, I was obsessed with Shirley Temple. I watched all her movies, and while I watched I stood in front of the television and fastidiously tried to learn her dance moves. To this day, the area of carpet directly in front of the television is more worn than the rest of the carpet in my family’s living room. Whenever my family went out to eat, I always ordered a Shirley Temple (a non-alcoholic drink made with Sprite, grenadine, and topped with a maraschino cherry). Although Temple’s infamous ringlets were red, I structured my curls to mimic hers. My parents indulged me as they loved to watch me tap dance around the house. They bought me every Temple movie available on VHS and smiled at my gleeful reaction as I ran to play each new tape.

One typical Saturday, I was dancing along to a newly-acquired Temple movie. My Dad came downstairs and stood watching me for a minute, laughing at my spastic movements. Then he turned to look at the movie more closely. As he continued to watch, his eyebrows furrowed in confusion. His confusion quickly turned to anger.

“Turn it off,” he said. I continued dancing.

“Turn it off,” he repeated. I kept dancing.

“Why, Daddy?” I asked.

“Mikayla,” he said sternly, “I am not going to tell you again. Turn that off.”

“But I’m watching it!”

“Well you can’t watch it anymore,” he responded, his voice starting to rise.

My Mom, hearing the loud voices, came in to the living room.

“What’s going on?” she asked.

“She needs to turn that movie off. Now,” my Dad said to her.

“Why? What’s wrong with it?” my Mom pressed.

“Just look at it.”

My Mom stood and watched the movie for a few moments. Her eyebrows furrowed in similar confusion to my Dad’s. But her expression did not turn to anger. She turned to my Dad.

“I don’t get it,” she said, “what’s wrong?”

My Dad looked at her with a hurt look that I had never seen cross his face before. He shook his head.

“I’ll explain later,” he said. “Just trust me on this, alright?”

He ejected the tape from the player and walked upstairs. I never saw it again.

***

I did not think anything about that incident until I started working on this paper. I did not understand why my Dad got so upset about the movie, and he never explained his reaction to me. When I started my project, I began with a search in to the Uncle Tom stereotype and the proliferation of it throughout popular culture. I quickly learned that the Uncle Tom Harriet Beecher Stowe described in Uncle Tom’s Cabin radically differs from the “Uncle Tom” known to most today. The Merriam Webster dictionary defines “Uncle Tom” as “a black who is overeager to win the approval of whites (as by obsequious behavior or uncritical acceptance of white values and goals); a member of a low-status group who is overly subservient to or cooperative with authority” (Merriam-Webster online dictionary, n.d.). The protagonist of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, however, is not like this. He is not “overly subservient” to whites. He willingly sacrifices himself and his well-being to help others, white or black.

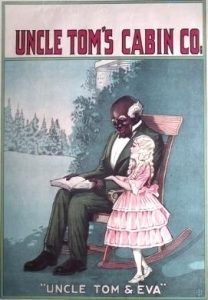

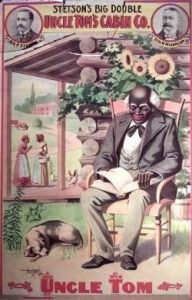

Yet negative images associated with “Uncle Tom” flourished in the post-war years. These images came from minstrel shows of white men playing Uncle Tom in blackface as a fool or an apologist for slavery (Stowe Center, UTC and American Culture). Stowe described Uncle Tom as a strong, muscular man, but the productions showcased Uncle Tom as a weak, old man with grey hair, a receding hairline, and a cane. These “Tom Shows” as they were called denied Uncle Tom the agency he had in the book as a powerful individual who could fight for resistance. Professional “Tom Shows” toured annually for about ninety years following the book’s publication in 1852 and some versions were filmed for movies and cartoons.

“Tom Shows” put Uncle Tom’s Cabin in to the popular imagination in a way that infantilized and trivialized the slave experience. Images of a happy, submissive older black man flooded twentieth-century cultural forms, including Shirley Temple movies. As I researched for this project, I came across information about Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, an actor in many Shirley Temple movies. Robinson was an older black man who often tap danced alongside Temple. Their relationship mirrors the one between Uncle Tom and Eva in Uncle Tom’s Cabin. The 1935 Shirley Temple movie The Little Colonel features a big dance number. Temple is the star of the number and Robinson supports her as Temple’s backup dancer. The film showcases the narrative of an older, subservient black man happily deferring to the needs of a privileged white child.

The Little Colonel, as it turns out, is the movie my Dad stumbled upon me watching all those years ago. His angry reaction to the film came from seeing yet another image of an “Uncle Tom” playing out in front of him. He did not want to see a negative depiction of a black man on the television in his home and he did not want his impressionable daughter seeing the image as well. My Mom did not initially understand my Dad’s issue with the film. My Mom is white and my Dad is black. She was not aware of the “Uncle Tom” stereotype and the issues my father had with it. I was little and did not understand what was going on. But now that I know about the stereotype and the images associated with it, I see how pervasive they are in our national culture.

***

Most of the rides at Disney World are based off a popular Disney movie—the Dumbo ride from the movie of the same title, the Buzz Lightyear Adventure from Toy Story, and Star Tours from Star Wars. But the origins of one of Disney World’s most popular rides, Splash Mountain, remain unknown to most Americans. Splash Mountain has always been my favorite ride. It is a log water attraction with outdoor and dark interior portions culminating in a fifty-foot drop into cold water. Splash Mountain tours riders through three adventures of Brer Rabbit, a cunning trickster who uses his wit to escape his enemies, Brer Fox and Brer Bear. In the first adventure, Brer Rabbit craftily dodges a snare trap and uses it to trap Brer Bear instead. The log ride continues as Brer Rabbit finds his “laughing place”, closely followed by Brer Fox and Brer Bear. Instead of leading them to this fictitious spot, however, Brer Rabbit leads his adversaries into a beehive. In the third and final scenario, Brer Fox finally captures Brer Rabbit and plans to roast him. Using reverse logic, Brer Rabbit convinces Brer Fox to throw him into the briar patch (mimicked in the ride by the legendary fifty-foot drop). Brer Rabbit and the riders escape unscathed (save for some wet clothing) as Brer Rabbit exclaims, “I was born and raised in the briar patch!”

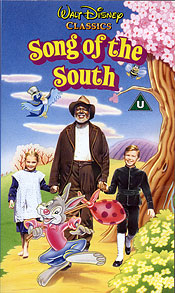

Few of the attraction’s riders know the basis of the ride’s story and characters and its complicated racial past. I wrote about this complicated past in a final paper for a history seminar I took in the fall of 2015 titled “Problems with American Historical Memory: The Civil War”. Splash Mountain is modeled after Disney’s 1946 hybrid live action and animated film Song of the South, which is based on Joel Chandler Harris’s Uncle Remus and Brer Rabbit stories. The film also features the familiar Disney ditty “Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah”, sung by James Baskett. Baskett played the film’s protagonist, Uncle Remus, a black former slave living and working on a plantation in Georgia. After several reissues, the film disappeared from circulation after its 1986 release because of its racial controversy. Today, the Disney Corporation markets only the non-racialized portions of the film, such as “Zip-A-Dee-Doo-Dah” and Splash Mountain rather than the negative depictions and stereotypes demonstrated by the Uncle Remus character.

Disney disguises the racial undertone of Song of the South, but doing so perpetuates the power we grant stereotypes. Rather than try to understand where a stereotype may come from and fight against it, we either accept it or we try to push it from the public discourse. My Dad did this when he told me to turn off The Little Colonel rather than teach me about the issues he had with it. If we do not learn from stereotypes, we can never seek to correct them.

Walter Lippmann, an American writer and political commentator, coined the term “stereotype” in popular discourse in his 1922 book Public Opinion. Stereotypes, he writes, provide a distorted mental picture of reality because “we are told about the world before we see it” (Soares, 51). “For the most part,” Lippmann writes, “we do not see and then define; we define first and then see. In the great blooming of the outer world we pick up what our culture has already defined for us, and we tend to perceive that which we have picked out in the form stereotyped for us by our culture,” (Soares 51). Cognitively, it is easy for us to accept a stereotype because it is a way of seeing the world that “our culture has already defined for us”. We learn stereotypes at a young age and they then influence how we see the world. Children “pick up” stereotypes and are often just told that these stereotypes are “bad” without learning why. They deserve to know the why, which is what I sought to do in my final project.

***

The first recorded instance of use of the term “Uncle Tom” as a derogatory slur was in a 1919 speech made by political leader Marcus Garvey to a crowd of black Americans. “From 1914 to 1918,” he said, “two million Negroes Fought in Europe for a thing foreign to themselves—Democracy. Now they must fight for themselves. The time for cowardice is past. The old-time Negro has gone—buried with ‘Uncle Tom.’” (Garvey, The Afro-American). The term “Uncle Tom” is often used within the black community to critique the behavior of a black person in relation to the white race. A. Philip Randolph popularized the term in his advocacy for the creation of a union for Pullman Porters. He created the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters to support the workers’ rights and lambasted the black workers who did not join the union. In a 1925 political pamphlet he wrote, “The handicap under which the porters are now laboring are due to the fact that there are too many Uncle toms in the service. With their slave psychology they bow and kowtow and lick the boots of the Company officials, who either pity or despise them” (Randolph, The Messenger).

The image of an Uncle Tom as a weak, submissive figure stems from the “Tom Shows” performed to American audiences across the country. This Uncle Tom is not, however, the one Stowe wrote in her book. Stowe employs Christianity in her abolitionist narrative for Uncle Tom’s Cabin. In so doing, she makes Uncle Tom a Jesus-like martyr figure. Uncle Tom dies because his master, Simon Legree, beats him to death after Uncle Tom refuses to betray the whereabouts of two female slave runaways. His passivity is thus a character strength, not a weakness. He does not “bow and kowtow and lick the boots” of his master. Instead, in the ultimate test, he protects his race.

Stowe glorifies Uncle Tom as the ultimate hero of the novel and champions his behavior as a model of behavior for all people, regardless of race. Uncle Tom is self-sacrificing because of the love and respect he feels for the people around him. It was radical for Stowe to equate a black character to Jesus. “Tom Shows” were white Americans’ attempts to undercut the social validity Stowe gave Uncle Tom. But in the novel, Uncle Tom is the redeemer. His name should not be the one with negative connotations. If any name should be a derogatory term, it should be Simon Legree.

***

The original conception for my final project was to provide a space for teaching the truth of Uncle Tom’s Cabin to a young audience. Children are impressionable and subject to quickly adopt any observed stereotypes. As a child I did not know what was wrong with The Little Colonel, but in recent years I learned about the negative imaging of older black male figures such as Bojangles Robinson. Additionally, I enjoyed Splash Mountain for many years without any knowledge of the movie behind it. I wanted my project to be an intervention into a popular culture where negative imagery of “Uncle Toms” surrounds us, perhaps in an even more pervasive form than we recognize.

I initially struggled to find a “voice” for writing this children’s book. I only started to take creative writing courses at Yale in my sophomore year when I took Daily Themes. Following that course, I took Playwriting and Screenwriting. Writing for children, however, is markedly different from these other writing forms. In Playwriting and Screenwriting we learned about writing in voices separate from our own, but even in those courses I created characters somewhat like me. Both my play and screenplay covered the lives of high school and college-aged individuals, so the dialogue I created mirrored that of the people around me. As a college student, however, I do not spend much time with children so writing in a language understandable to them proved difficult.

I turned to contemporary children’s books to aid in my pursuit of finding a narrative language. Some of these books were: Where the Wild Things Are, Goodnight Moon, and Blueberries for Sal. Ultimately, I decided that my target audience would be children aged 6-8. I figured this would be an age demographic that had some knowledge about what slavery was. It was also particularly important for me to find books specifically written for black children, such as Happy to be Nappy and If I Ran for President, since I planned to write my children’s book with a black audience in mind. I wanted my children’s book to be a celebration of Uncle Tom rather than a criticism of Stowe and the negative images associated with the notion of an “Uncle Tom” today.

Children’s stories often have a very clear moral. For my children’s book, The True Story of Uncle Tom, I wanted to streamline the moral Stowe laid out in her novel to make it even more explicit. Stowe grounds her case for abolition in Christianity. She makes Uncle Tom a Jesus-like figure who in the end shows everyone the importance of forgiveness. As Uncle Tom is being beaten to death, he opens his eyes and looks at Legree and says, “Ye poor miserable creature! There ain’t no more that ye can do! I forgive ye, with all my soul.” In Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Stowe created fully developed black characters. She made the slaves humans rather than property to show people the immorality of slavery. The ability to forgive is crucial in Stowe’s story as she shows that it is a characteristic that transcends race. In making Uncle Tom the hero of the story, Stowe shows that he is a human everyone should respect and admire rather than a slave who can be subjected to mistreatment and humiliation.

***

The main limitation of my children’s story is my inability to produce illustrations. I consider myself a creative person, but not when it comes to the visual arts. Last year, I took a seminar called “Mastering the Art of Watercolor”. The Professor was nice and helpful, but he eventually encouraged me to develop more “abstract” and “modern” art since my attempts at any literal depictions of Yale University’s gothic architecture failed. Illustrations are essential components to children’s books as they give children visuals to aid in their understanding of the words on the page. They make the story fun and beautiful in a way lost in adult novels. If I were to try to publish my book, or to pursue the craft of writing for children, I would find a collaborator to create my illustrations. Most children’s books are collaborations between an author and an illustrator. I would look forward to working with an artistic partner to create a balance of words and pictures appealing to a young eye.

As a child, my favorite time of day was when my Mom would come and read to me before bed. She read simply, without crazy voices or anything of that sort, but something about the soothing sound of her voice lulled me to sleep. When I worked as an assistant teacher at a kid’s camp a few years ago, we spent an hour every day reading to the children. Children learn to read and, at least in my experience, learn to love to read through hearing books read out loud to them. To this day, I love to listen to audiobooks because I think the addition of a human voice to a story adds a layer of depth inaccessible by the simple written word. That is why I decided to provide an audio recording of myself reading The True Story of Uncle Tom. I think my narration supplements the story and adds to the experience of understanding the tale.

If I had full time and resources, I would make an animated movie of The True Story of Uncle Tom. To this day, I love animated films. I think they are a great source of entertainment for children and adults alike. My dream job would be to write a Disney movie as I believe I have a very childlike sense of humor. Maybe that will be something I pursue, and The True Story of Uncle Tom would have just been the start. We’ll see what comes next…

Below are some images that guided me through my research. I would provide these images to an artist as inspiration for a collaborative illustrated book of The True Story of Uncle Tom.

Harry Birdoff Collection, Harriet Beecher Stowe Center. “I Is Uncle Tom. I Won’t Hurt You”. Color lithograph poster for stage production. http://utc.iath.virginia.edu/saxon/servlet/SaxonServlet?source=utc/xml/media/onstage-images/ostspostrs.xml&style=utc/xsl/utcprint.xsl&print=yes.

Harry Birdoff Collection, Harriet Beecher Stowe Center. “Uncle Tom and Eva”. Color lithograph poster for stage production. http://utc.iath.virginia.edu/saxon/servlet/SaxonServlet?source=utc/xml/media/onstage-images/ostspostrs.xml&style=utc/xsl/utcprint.xsl&print=yes.

Harry Birdoff Collection, Harriet Beecher Stowe Center. “Uncle Tom”. Color lithograph poster for stage production. http://utc.iath.virginia.edu/saxon/servlet/SaxonServlet?source=utc/xml/media/onstage-images/ostspostrs.xml&style=utc/xsl/utcprint.xsl&print=yes.

Disney Corporation. Song of the South. Cover Art. http://www.snopes.com/disney/films/sots.asp.

Disney Corporation. Song of the South. Uncle Remus and the Kids. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Song_of_the_South#/media/File:Remuskids.jpg.

Fox Film. The Little Colonel. Shirley Temple and Bill “Bojangles” Robinson. Released February 22, 1935. http://black-face.com/Bill-Bojangles-Robinson.htm.

Encyclopedia Britannica. “Bill Robinson”. Published March 3, 2017. https://www.britannica.com/biography/Bill-Robinson.

Work Cited

Garvey, Marcus. “Garvey Urges Organization”. The Afro-American. Baltimore: 28 February 1919. Accessed 29 April 2017. http://utc.iath.virginia.edu/africam/afar93at.html.

Harriet Beecher Stowe Center. “Uncle Tom’s Cabin and American Culture”. 2015. Accessed 27 April 2017. https://www.harrietbeecherstowecenter.org/utc/american_culture.shtml.

Randolph, A. Philip. “Pullman Porters Need Own Union”. New York: August 1925. Accessed 29 April 2017. http://utc.iath.virginia.edu/africam/afes92at.html.

Soares, Isanilda. “Racial Stereotypes in Fictions of Slavery: Uncle Tom’s Cabin by Harriet Beecher Stowe and O Escravo by José Evaristo D’ Almeida”. Dissertation for the Universidade de Coimbra, 2013.

“Uncle Tom.” Merriam-Webster.com. Merriam-Webster, n.d. Web. 2 May 2017.